On Tuesday, December 18, 2017, the United States Food and Drug Administration approved the first ever gene therapy for an inherited disease. Patients with a type of Leber congenital amaurosis (LCA), a blinding childhood eye disease, due to mutations in the RPE65 gene will now be able to receive treatment to improve their sight. This is a landmark day, and one which countless scientists, physicians, and patients have worked toward for decades.

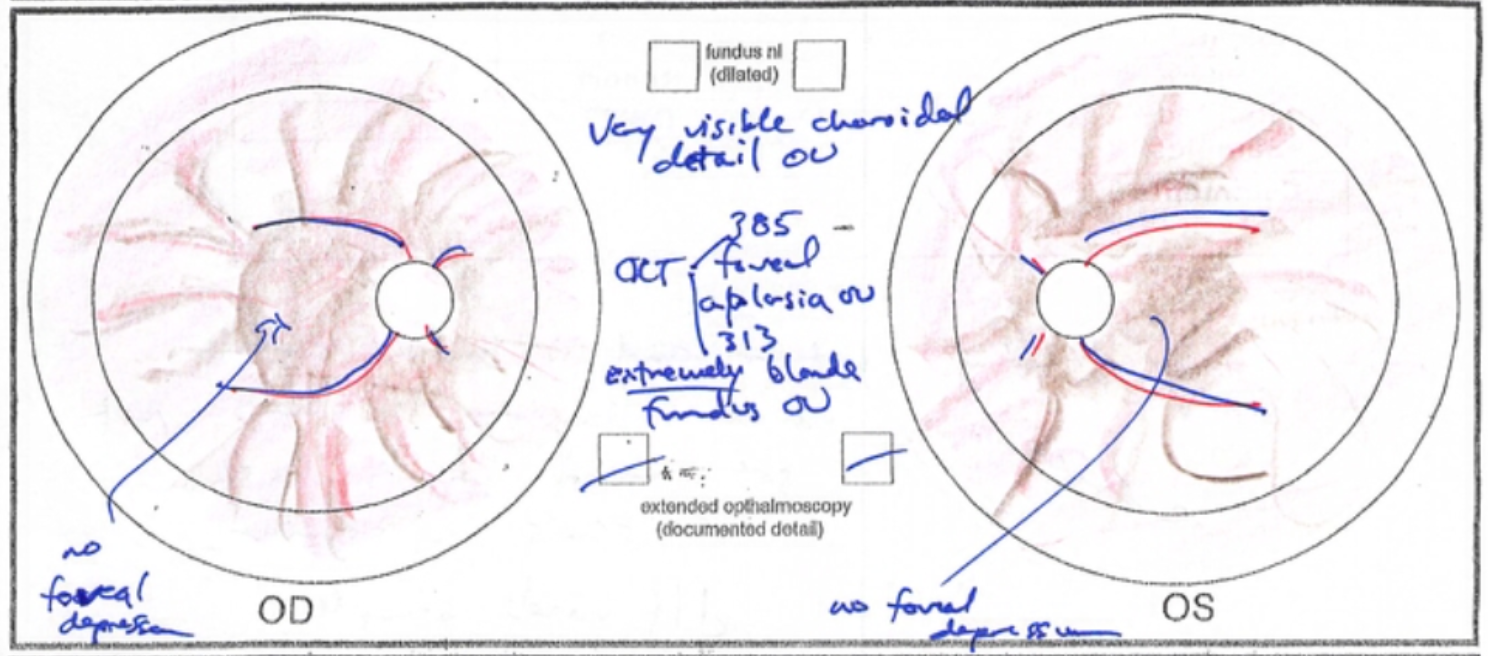

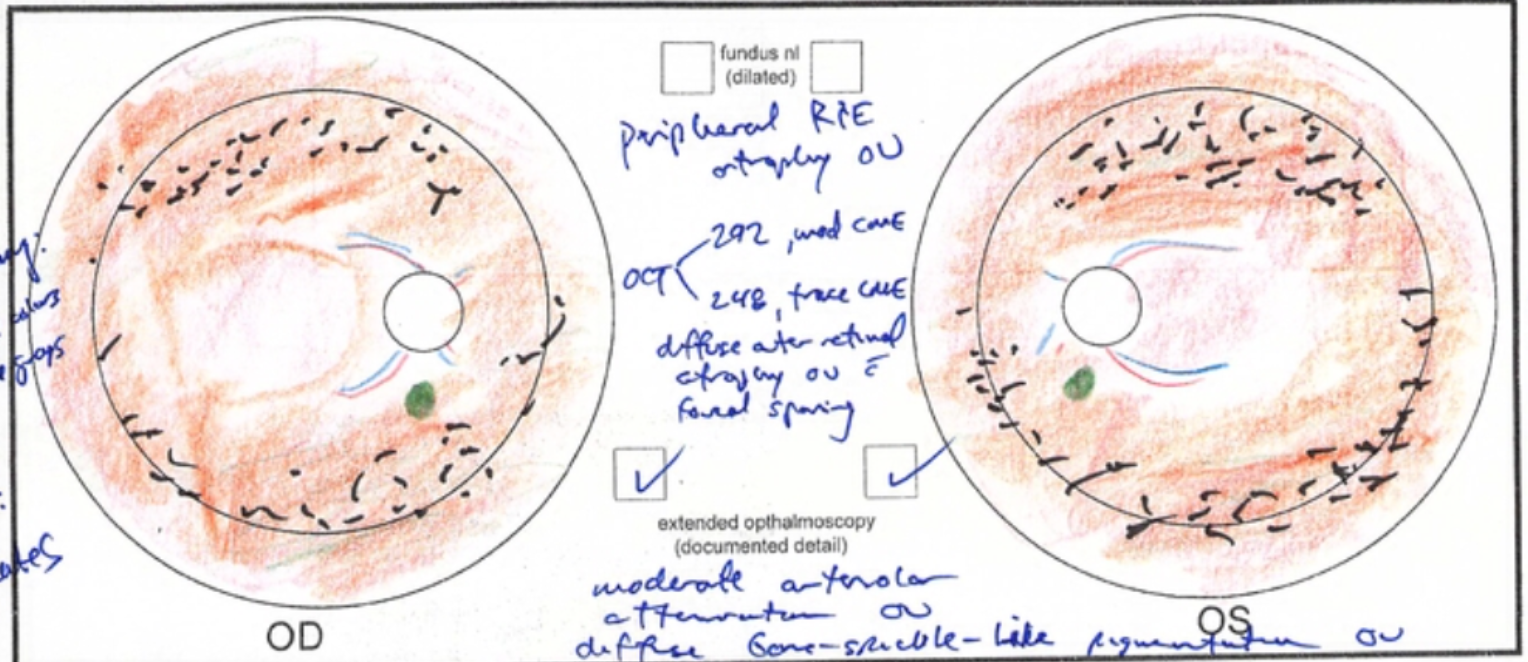

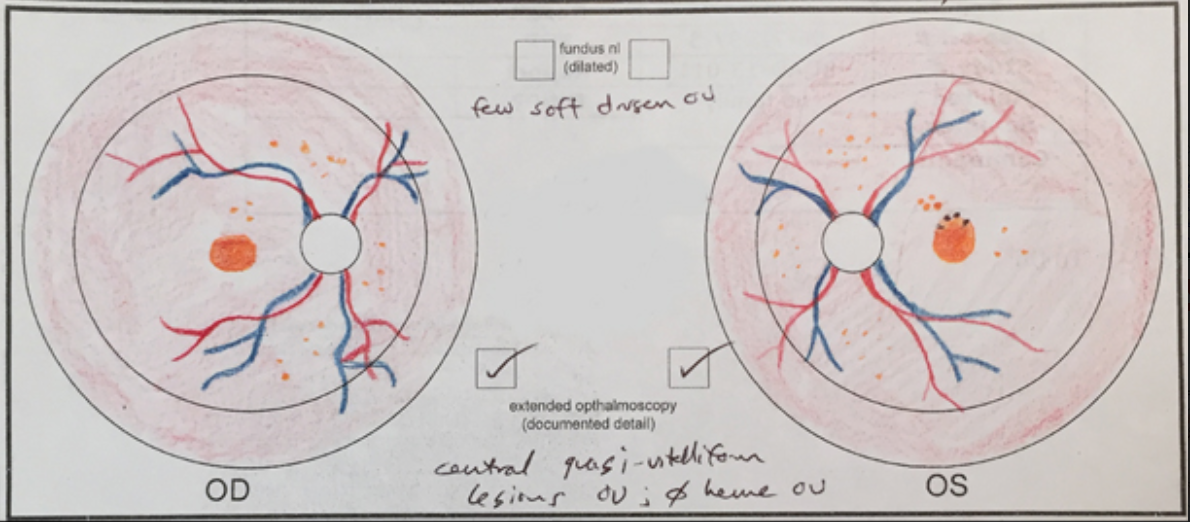

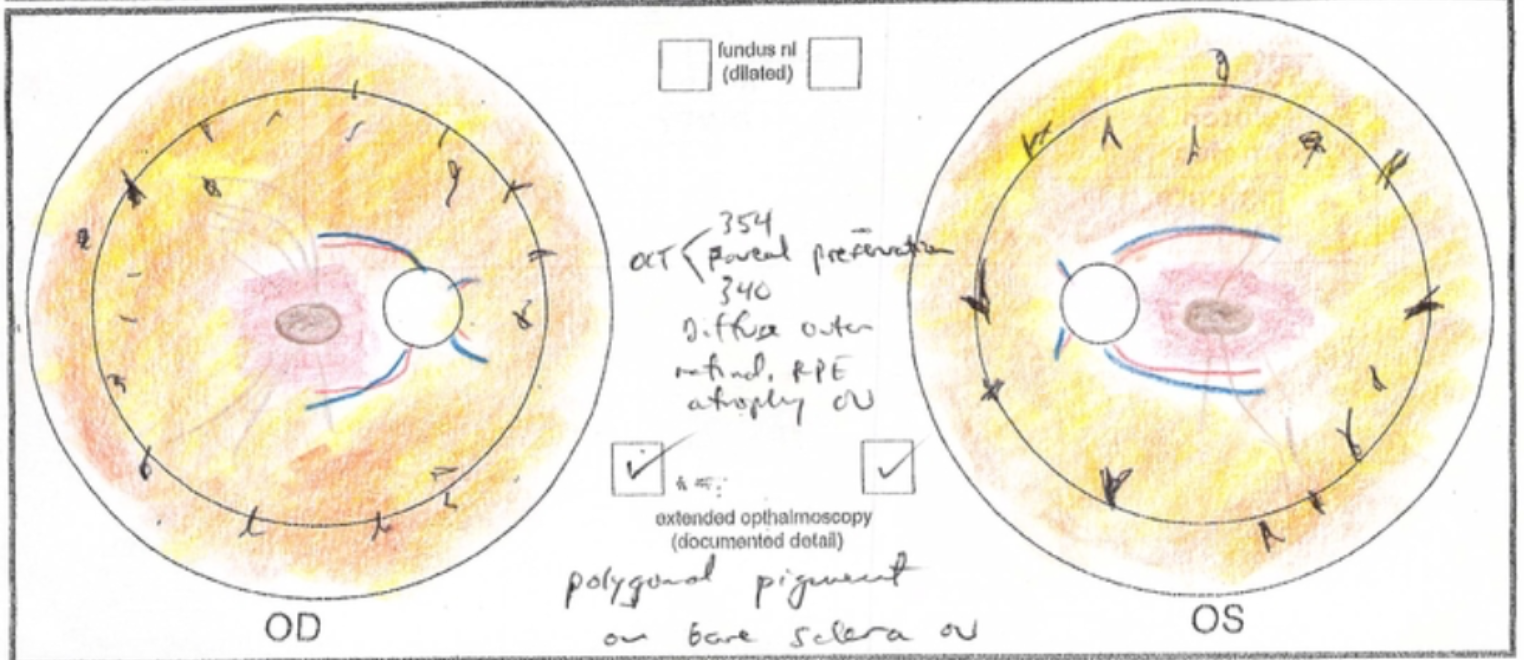

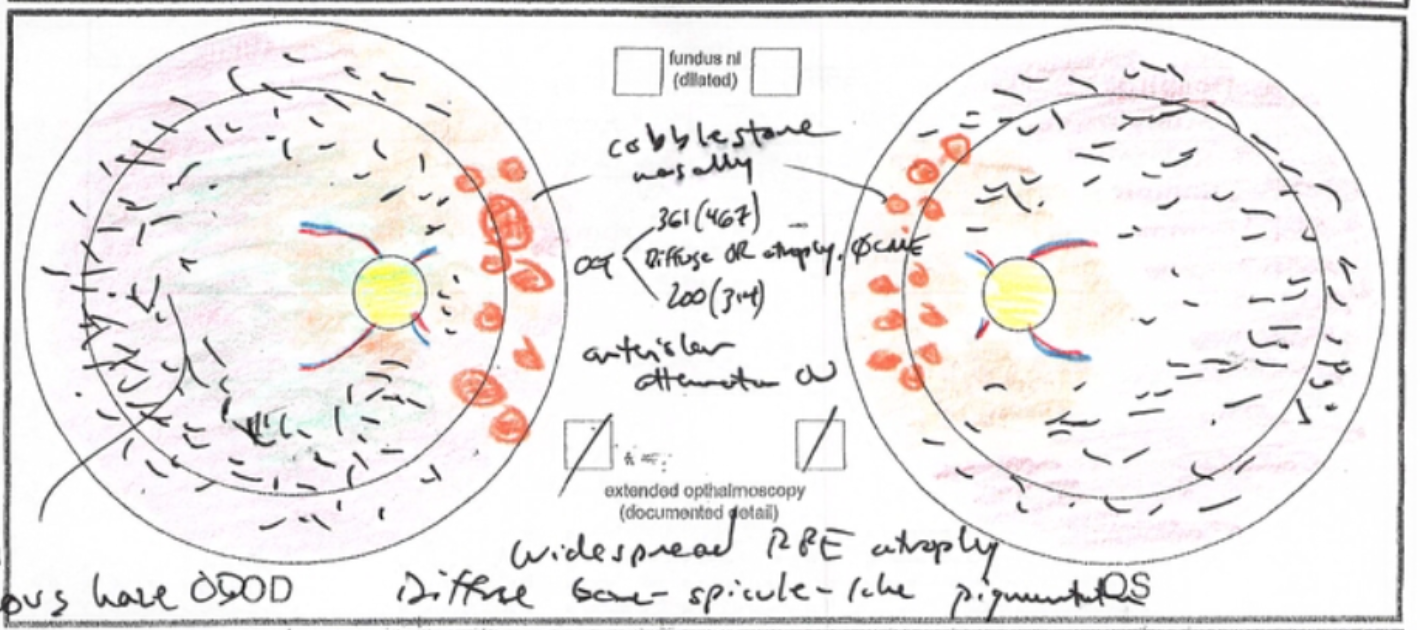

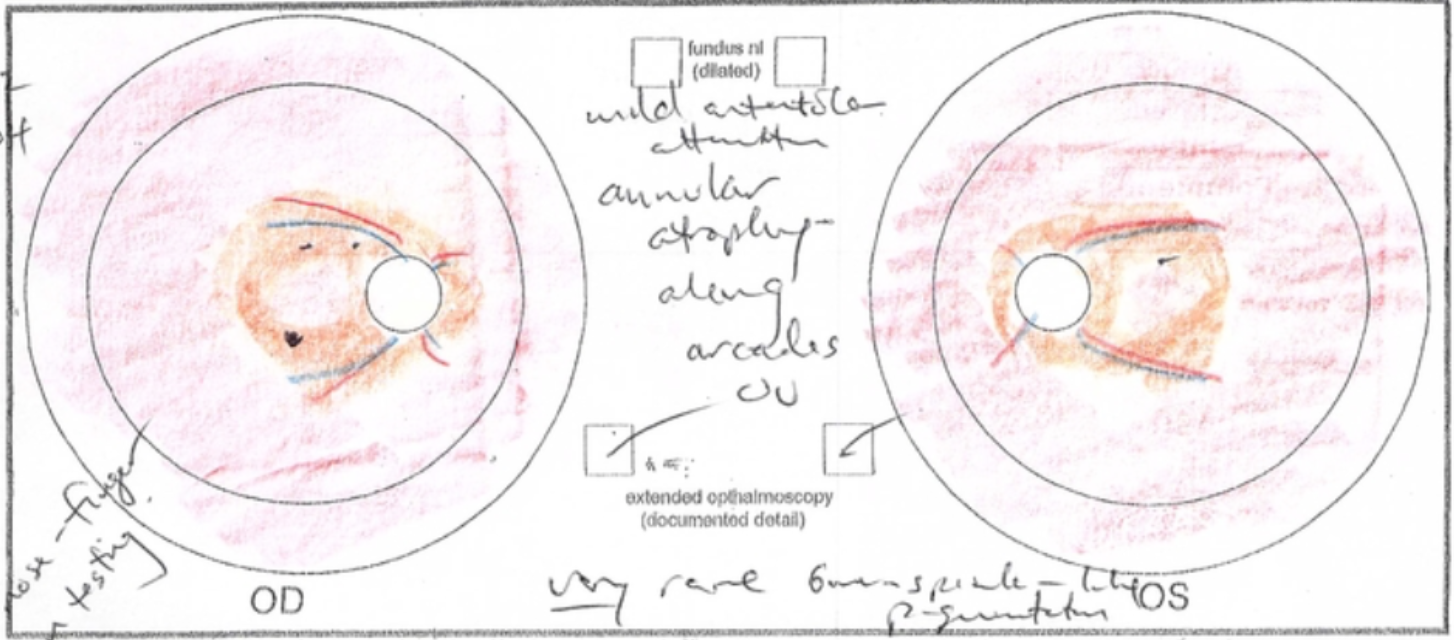

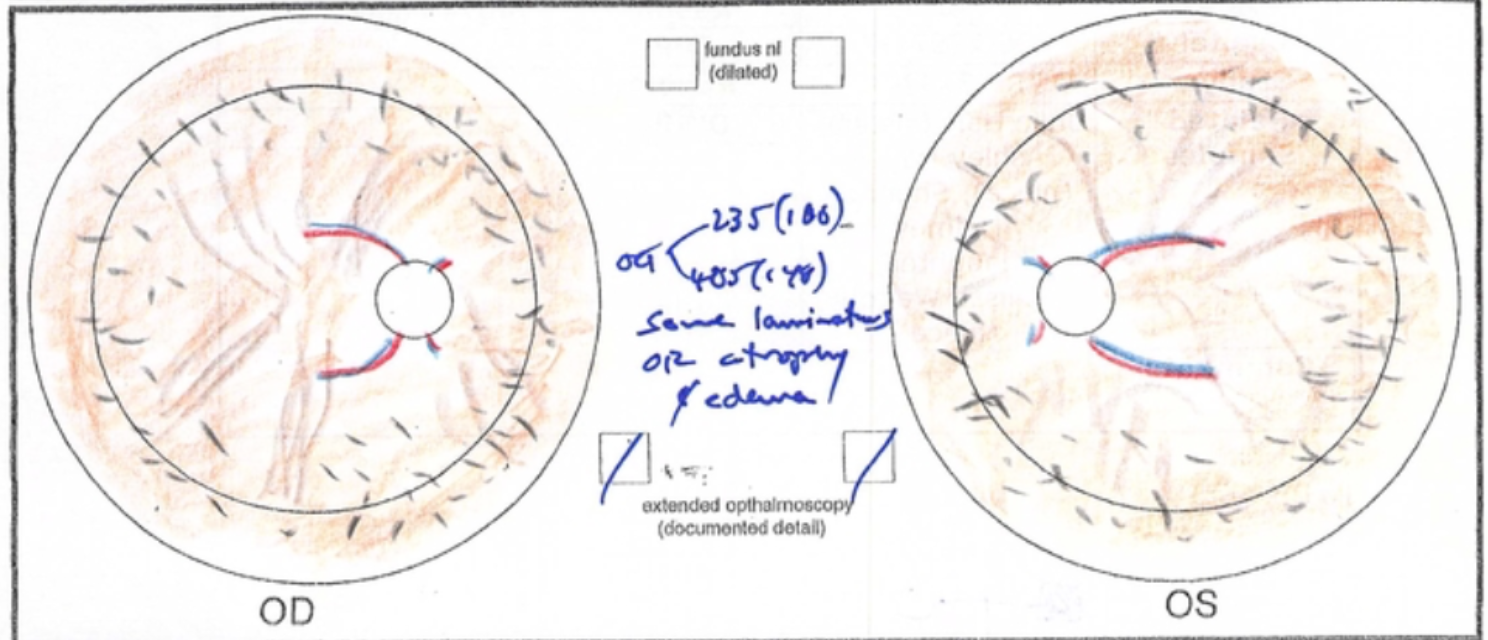

LCA is a genetic condition which causes severe vision loss and blindness in childhood. Affected children are often born with very poor vision, and parents may notice their child never seems to make eye contact, has roving eye movements, or nystagmus, where the eyes shake back and forth. Almost all LCA is autosomal recessive, meaning each parent is a carrier for the disease, that each child of these two parents will have a 25% risk of developing the disease, and that affected individuals have a <1% chance of passing it on to their future children. Until the late-2017 FDA approval of voretigene, there were precisely zero commercially-available treatments for LCA.

Fortunately, and miraculously, this is changing.

Scientists have developed a treatment, called voretigene neparvovec (Luxturna is the trade name), which can be given to patients with this specific type of LCA. This treatment is a type of gene therapy, which means that the correct version of the defective gene is given to the patient, allowing the RPE65 protein product to perform its normal function in the eyes (RPE65 is an enzyme involved in recycling Vitamin A in the visual cycle).

Voretigene makes use of a benign virus to carry the correct version of the RPE65 gene into the patient's eyes. The patient undergoes a surgery, under general anesthesia, during which voretigene is injected very carefully, by highly trained vitreoretinal surgeons, underneath the retina.

I have seen several patients who underwent this treatment during voretigene's clinical trial. I was very impressed with the results -- children with no functional vision were suddenly able to see well enough to navigate the room. Results from the phase 3 clinical trial were published recently in the prestigious journal Lancet, with my friend and training mentor Dr. Stephen Russell of the University of Iowa as the lead author.

Voretigene represents a historic breakthrough on multiple levels. Not only is it the first medical treatment for a previously untreatable disease, allowing blind people to see for the first time, but it is also the first gene therapy for an inherited disease of any kind. It will also pave the way for future research and development of similar treatments for similar diseases. As a pediatric ophthalmologist and inherited eye disease specialist, it is difficult to overstate how excited I am about this!

Curious as to what kind of a difference this treatment can really make? Check out these next two videos. The first shows a boy with RPE65-LCA trying to navigate an obstacle course prior to his treatment. Notice how much he struggles.